Hierarchical module naming schemes¶

Up until now we have used EasyBuild's default module naming scheme (EasyBuildMNS),

which produces module files with names that closely resemble to the names of the

corresponding easyconfig files.

For example, when installing Bowtie2-2.4.1-GCC-9.3.0.eb the generated module was named Bowtie2/2.4.1-GCC-9.3.0.

EasyBuild supports several different module naming schemes:

$ eb --avail-module-naming-schemes

List of supported module naming schemes:

CategorizedHMNS

CategorizedModuleNamingScheme

EasyBuildMNS

HierarchicalMNS

MigrateFromEBToHMNS

In this part of the tutorial we will take a closer look at HierarchicalMNS,

which is the standard hierarchical module naming scheme included with EasyBuild.

Flat vs hierarchical¶

The default module naming scheme EasyBuildMNS is an example of regular "flat" module naming scheme, which is characterized by:

- all module files are directly available for loading;

- each module name uniquely identifies a particular installation;

In contrast, a hierarchical module naming scheme consists of a hierarchy of module files.

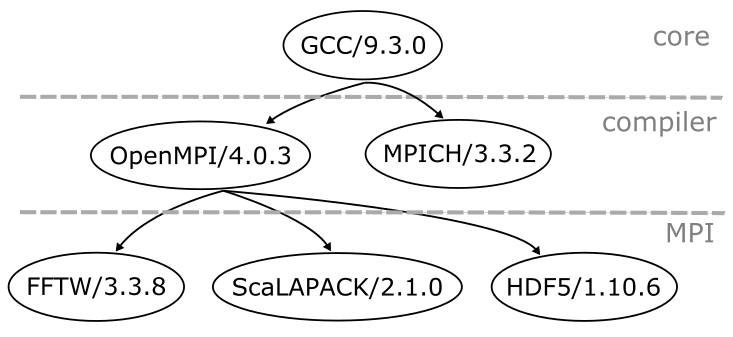

The typical module hierarchy has 3 levels:

- a core level, where module files for software that was installed using the

systemtoolchain are kept; - a compiler level, where module files for software that was installed using a compiler-only toolchain are stored;

- and an MPI level, which houses module files for software that was installed using a toolchain that includes (at least) a compiler and MPI component;

Here is a simple example of such a 3-level module hierarchy:

In this example the core level only includes a single module GCC/9.3.0,

while the compiler level includes two modules: OpenMPI/4.0.3 and MPICH/3.3.2.

In the MPI level, three modules are available: one for FFTW, one for ScaLAPACK, and one for HDF5.

As you will notice, at every level we select the module of the layer we are entering. At core level we

select our compiler. When in the compiler level we select our MPI implementation, and within the MPI

level we select our software.

Initially only the modules on the top level of a module hierarchy are available for loading.

If you run "module avail" with the example module hierarchy, you will only see the GCC/9.3.0 module.

Some modules in the top level of the hierarchy act as a "gateway" to modules in the

next level below.

To make additional modules available for loading one of these gateway modules has to be loaded. In our exampe, loading the GCC/9.3.0 module results in two additional modules coming into view from the compiler level, as indicated by the arrows: the modules for OpenMPI and MPICH. These corresponds to installations of OpenMPI

and MPICH that were built using GCC/9.3.0 as a toolchain.

Similarly, the OpenMPI/4.0.3 module serves as a gateway to the three modules in the MPI level. Only by loading the OpenMPI module will these additional three modules become

available for loading. They correspond to software installations built using the gompi/2020a toolchain that

consists of the GCC/9.3.0 compiler module and the OpenMPI/4.0.3 MPI module. Software installing using

foss/2020a (which is a full toolchain that also includes OpenBLAS, FFTW and ScaLAPACK) would also be stored

in this level of the module hierarchy.

The characteristics of a module hierarchy are:

- not all module files are directly available for loading;

- some modules serve as a gateway to more modules;

- to access some software installations you will first need to load one or more gateway modules in order to use them;

You can probably think of other ways to organize module files in a hierarchical module tree, but here we will stick to the standard core / compiler / MPI hierarchy.

Pros & cons¶

So why go through all this trouble of organizing modules hierarchically?

There are a couple of advantages to this approach:

- shorter module names;

- less overwhelming list of available modules;

- only compatible modules can be loaded together;

However, the are some minor disadvantages too:

- not all existing modules are directly visible;

- gateway modules may have little meaning to end users;

Length of module names¶

When using a flat module naming scheme, module names can be fairly long and perhaps confusing. For our HDF5 installation for example,

we have HDF5/1.10.6-gompi-2020a as module name. The -gompi-2020a part of the name refers to the toolchain that was

used for this installation, but it may be confusing to some people (what kind of Pokémon is a "gompi"?!).

In the example module hierarchy shown above, the module for HDF5 is named HDF5/1.10.6 which is basically the bare

essentials: software name and version. That's way better, nice and clean!

Amount of available modules¶

The output of "module avail" can be quite overwhelming if lots of module files

are installed and a flat module naming scheme is used, since all modules are

always available.

EasyBuild makes it very easy to install lots of software,

so the number of installed modules can quickly grow into the hundreds or even thousands! Yikes!

This often explosive growth of modules is less of an issue when using a hierarchical module naming scheme, since initially only a modest set of modules are available, and relatively small groups of additional modules become available as gateway modules are loaded.

Loading compatible modules¶

Since all modules are available at once when using a flat module naming scheme, you can easily load modules together that are not compatible with each other.

Imagine loading two modules that were built with a different compiler toolchain (different compiler, different MPI library). That's likely to end in tears, unless you have the necessary technical expertise and you are being very careful...

In a module hierarchy this can be prevented, since modules for software that was installed with a different compiler and/or a different MPI library is located in a different part of the module hierarchy, and thus these modules will be prevented from being loaded together.

Visibility of existing modules¶

One downside of a module hierarchy is that not all existing modules are directly available for loading

or are even visible to the user, since the output of "module avail" only shows a subset of all modules.

Lmod has a solution for this though: it provides a separate "module spider" command to search

for module files throughout the entire module hierarchy. So as long as the end users are aware of this

additional command, it should not be difficult to discover which software installations exist and how

they can be accessed. The "module spider" command will inform the user which of the gateway modules

need to be loaded in order to load a specific module file.

Semantics of gateway modules¶

An additional potential problem of a module hierarchy is that the semantics of the gateway modules may not be clear to end users. They may wonder why they need to pick a specific compiler and MPI library, or which of the available options is the best one. Maybe there are not even be aware what exactly a "compiler" is, or how it is relevant to the software they need in their bioinformatics pipeline...

This can be partially resolved by loading a default compiler and MPI module so a particular set of modules

is available right after login, which could be the ones used in the most recent toolchain, or the

recommended versions. More experienced users could then leverage the "module spider" command to navigate

the module hierarchy.

Example¶

Warning

This example will not work when running the prepared container

image using Singularity,

because the /easybuild directory is read-only in this case,

and EasyBuild still requires write access to /easybuild/software

even when generate module files outside of /easybuild.

Now that we know more about hierarchical module naming schemes, let us see how EasyBuild can help us with generating a hierarchical module tree.

In this example we will use EasyBuild to generate modules organised in a hierarchy for some of the software that is already installed in the prepared environment.

The good news is that the existing installations can be reused. There is absolutely no need to reinstall the software, we are just creating a different "view" on these software installations.

Preparing the environment¶

Before running EasyBuild to generate a hierarchical module tree, we have to be a bit careful with preparing our environment.

We must absolutely avoid mixing modules from a flat and hierarchical module naming scheme!

Some module files will have the same name in both module trees (like GCC/9.3.0 for example),

but their contents will be different.

Mixing modules from a flat and hierarchical module tree will trigger problems...

So we have to make sure that the module files we already have in /easybuild are not visible.

The easiest way to do this is to unload all modules (using "module purge")

and resetting the module search path to be empty, which we can do with "module unuse $MODULEPATH".

module purge

module unuse $MODULEPATH

In this part of the tutorial, we are assuming you are not using an EasyBuild installation provided through a module. We have just made all modules unavailable, so we would have to first install EasyBuild again in our hierarchical module tree before we can continue.

We strongly recommend using an EasyBuild installation that was installed via "pip install"

or "pip3 install" in this part of the tutorial.

An easy way to do this is in the prepared environment is to run:

pip3 install --user easybuild

export PATH=$HOME/.local/bin:$PATH

export EB_PYTHON=python3

Configuring EasyBuild¶

First of all, we need to make sure that EasyBuild is properly configured. We can do this by defining this set of environment variables:

export EASYBUILD_PREFIX=$HOME/easybuild

export EASYBUILD_BUILDPATH=/tmp/$USER

export EASYBUILD_INSTALLPATH_SOFTWARE=/easybuild/software

export EASYBUILD_MODULE_NAMING_SCHEME=HierarchicalMNS

export EASYBUILD_INSTALLPATH_MODULES=$HOME/hmns/modules

To make sure we didn't make any silly mistakes, we double check using eb --show-config:

$ eb --show-config

#

# Current EasyBuild configuration

# (C: command line argument, D: default value, E: environment variable, F: configuration file)

#

buildpath (E) = /tmp/example

containerpath (E) = /home/example/easybuild/containers

installpath (E) = /home/example/easybuild

installpath-modules (E) = /home/example/hmns/modules

installpath-software (E) = /easybuild/software

module-naming-scheme (E) = HierarchicalMNS

packagepath (E) = /home/example/easybuild/packages

prefix (E) = /home/example/easybuild

repositorypath (E) = /home/example/easybuild/ebfiles_repo

robot-paths (D) = /home/example/.local/easybuild/easyconfigs

sourcepath (E) = /home/example/easybuild/sources

There are a couple of things worth pointing out here:

- We have defined the

module-naming-schemeconfiguration setting toHierarchicalMNS, which makes EasyBuild use the included standard hierarchical module naming scheme (the classic core / compiler / MPI one we discussed above). - We have specified different locations for the software (via

installpath-software) and the module files (viainstallpath-modules). This is important because we want to reuse the software that is already installed in/easybuild/softwarewhile we want to generate an entirely new module tree for it (in$HOME/hmns/modules).

The other configuration settings are the same as before, and mostly irrelevant for this example.

Generating modules for HDF5¶

Let us now generate a hierarchical module tree for HDF5 and all of its dependencies,

including the toolchain. That sounds complicated, and it sort of is since there are

a lot of details you have to get right for the module hierarchy to works as intended,

but EasyBuild can do all the hard work for us.

The steps we will have to go through are:

- Tell EasyBuild we want to "install" the

HDF5-1.10.6-gompi-2020a.ebeasyconfig file; - Enable dependency resolution via

--robot; - Instruct EasyBuild to only generate the module files, not to install the software (since it is

there already in

/easybuild/software), via the--module-onlyoption.

These steps translate to this single eb command:

$ eb HDF5-1.10.6-gompi-2020a.eb --robot --module-only

...

== building and installing MPI/GCC/9.3.0/OpenMPI/4.0.3/HDF5/1.10.6...

...

== sanity checking...

== cleaning up [skipped]

== creating module...

...

== COMPLETED: Installation ended successfully (took 9 sec)

...

== Build succeeded for 37 out of 37

This should take about 2 minutes in total, for generating 37 modules. Remember that this also includes generating module files for the toolchain and all of its components.

In addition, there is a bit more going on one that just generating module files,

since the sanity check step is still being run for each of the installations

when using --module-only to ensure the installation is actually functional.

After all, there is no point in generating a module for an obviously broken

installation...

Loading the HDF5 module¶

After generating the hierarchical module tree for HDF5, how do we access the HDF5 installation through it?

Here's what the module tree looks like on disk:

$ ls $HOME/hmns/modules/all

Compiler Core MPI

Those are basically the 3 levels in the module hierarchy we showed in our example earlier.

The starting point is the top level of the module hierarchy named Core:

module use $HOME/hmns/modules/all/Core

Let us see what that gives us in terms of available modules:

$ module avail

--------------------- /home/easybuild/hmns/modules/all/Core ---------------------

Bison/3.3.2 GCCcore/9.3.0 flex/2.6.4 help2man/1.47.4

Bison/3.5.3 (D) M4/1.4.18 gettext/0.20.1 ncurses/6.1

GCC/9.3.0 binutils/2.34 gompi/2020a zlib/1.2.11

Nice and short module names, but only a limited set of them.

We know a module file exists for HDF5, but we can't see it yet (and hence

we can't load it either).

$ module avail HDF5

No module(s) or extension(s) found!

Use "module spider" to find all possible modules and extensions.

Let us see if module spider is of any help, as "module avail" so kindly suggests:

$ module spider HDF5

...

You will need to load all module(s) on any one of the lines below

before the "HDF5/1.10.6" module is available to load.

GCC/9.3.0 OpenMPI/4.0.3

This tells us we need to load two gateway modules before we can load the module for HDF5.

Let us start with loading the GCC compiler module:

module load GCC/9.3.0

And then check again which modules are available:

$ module avail

-------------- /home/easybuild/hmns/modules/all/Compiler/GCC/9.3.0 --------------

OpenMPI/4.0.3

------------ /home/easybuild/hmns/modules/all/Compiler/GCCcore/9.3.0 ------------

Autoconf/2.69 XZ/5.2.5 libtool/2.4.6

...

Szip/2.1.1 libpciaccess/0.16 zlib/1.2.11 (L,D)

UCX/1.8.0 libreadline/8.0

--------------------- /home/easybuild/hmns/modules/all/Core ---------------------

Bison/3.3.2 GCCcore/9.3.0 (L) flex/2.6.4 help2man/1.47.4

Bison/3.5.3 M4/1.4.18 gettext/0.20.1 ncurses/6.1

GCC/9.3.0 (L) binutils/2.34 gompi/2020a zlib/1.2.11

Good news, we now have additional modules available!

The compiler level of our hierarchy actually consists of two directories here: Compiler/GCCcore/9.3.0

and Compiler/GCC/9.3.0. The modules in the GCCcore directory are ones we can use in other compiler

toolchains that use GCC 9.3.0 as a base compiler (the details of that are out of scope here).

The module we are interested in is OpenMPI/4.0.3, which is another gateway module.

Remember that the "module spider" output told us that there does indeed exist a module for HDF5, but that

we need to load both the GCC/9.3.0 and OpenMPI/4.0.3 modules first.

So, let us do exactly that (remember that GCC/9.3.0 is already loaded):

module load OpenMPI/4.0.3

If you now check the output of "module avail" again, you should see the HDF5/1.10.6 module:

$ module avail

-------- /home/easybuild/hmns/modules/all/MPI/GCC/9.3.0/OpenMPI/4.0.3 -------

HDF5/1.10.6

------------ /home/easybuild/hmns/modules/all/Compiler/GCC/9.3.0 ------------

OpenMPI/4.0.3 (L)

...

To use HDF5, we just need to load this module. We can verify that the installation works

using one of the commands provided by HDF5, h5dump for example:

module load HDF5/1.10.6

$ h5dump --version

h5dump: Version 1.10.6

If you now check which modules are loaded via "module list", you will notice that all module names

and nice and short now, which is one of the advantages of using a hierarchical module tree:

$ module list

Currently Loaded Modules:

1) GCCcore/9.3.0 5) numactl/2.0.13 9) hwloc/2.2.0 13) HDF5/1.10.6

2) zlib/1.2.11 6) XZ/5.2.5 10) UCX/1.8.0

3) binutils/2.34 7) libxml2/2.9.10 11) OpenMPI/4.0.3

4) GCC/9.3.0 8) libpciaccess/0.16 12) Szip/2.1.1

Exercise¶

Now it is your turn!

Try to get a feeling for how a hierarchical module tree works by:

- installing the missing modules for the

SciPy-bundle-2020.03-foss-2020a-Python-3.8.2.ebin the module hierarchy we generated for HDF5; - figure out where the

SciPy-bundlemodule is located in the hierarchy, and then also load it;

You can verify your work by running this command (since pandas is one of the Python packages included

in the SciPy-bundle installation):

python -c 'import pandas; print(pandas.__version__)'

Start from a clean slate, by first running:

module purge

module unuse $MODULEPATH

(click to show solution)

-

Step 0: check which modules are still missing, using

--missingor-M:The output should tell you that 15 out of 50 required modules are still missing.eb SciPy-bundle-2020.03-foss-2020a-Python-3.8.2.eb -M -

Install the missing modules in the module hierarchy we have generated in

$HOME/hmns/modules:Don't forget to use botheb SciPy-bundle-2020.03-foss-2020a-Python-3.8.2.eb --robot --module-only--robot(to enable dependency resolution) and--module-only(to only run the sanity check and generate module files, not install the software again). -

Start at the top of the module hierarchy (the

Corelevel), and run module spider to check which gateway modules to load to makeSciPy-bundleavailable:module use $HOME/hmns/modules/all/Core module spider SciPy-bundle/2020.03-Python-3.8.2 - Load the gateway modules:

module load GCC/9.3.0 OpenMPI/4.0.3 - Check that the

SciPy-bundlemodule is available, and load it:$ module avail SciPy-bundle ----- /home/example/hmns/modules/all/MPI/GCC/9.3.0/OpenMPI/4.0.3 ------ SciPy-bundle/2020.03-Python-3.8.2module load SciPy-bundle/2020.03-Python-3.8.2 - Run the test command:

$ python -c 'import pandas; print(pandas.__version__)' 1.0.3

Warning

This exercise will not work when running the prepared container

image using Singularity,

because the /easybuild directory is read-only in this case,

and EasyBuild still requires write access to /easybuild/software

even when generate module files outside of /easybuild.